MODERNISM AND THE POINT OF MAN

The making up of the Modern mind

In this post I aim to introduce something of the idea of “modernism” in literature, to give the reader some idea of how the Errors were instituted in 20th century culture.

I hope it will be helpful for you to read this before we proceed to discuss Pascendi - the masterful analysis of the errors, causes, effects and remedy for the modern malaise, whose champions were determined to have its fantasies established in place of the facts.

This essay can be read as an effort to distinguish culture from civilisation, showing that the former is fabricated, whilst the latter is founded. There are entrances and exits and the point of Man is indicated by the end which defines our Being and Beginning.

I introduce and will return to the example of TS Eliot today, as his career and the development of his spiritual life is itself an object lesson in the reaction to the loss of God. His reply was atypical of the Moderns, because he wanted the truth.

I also go on about Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf, WB Yeats and Samuel Beckett, who were some of the leading lights of what is called Modernism in literature, and which in turn helped to form what we understand as Modern culture1.

They did not light the same path.

As Eliot pointed out, we can have better (or worse) fabricators of culture - but our civilisation has one cause. The fabulous culture we inhabit has many effects.

The idea overall is that these two can once again agree. What is in the way of that can be said to come from the Modern - whose thesis is that one thing can be made to replace another. Man in place of God being the main example. The inner life for the outer, the This for the That, the Self for Creator and all Creation.

This is a story about the Modern imagination.

WHAT IS THE POINT OF TS ELIOT?

It is hard not to go on about TS Eliot and today I hope to explain why.

Like most people who have heard of him I found his poetry difficult and occasionally striking, as if some great gong had been struck which resonated in a depth in myself I did not, until that booming note resounded, realise was there.

Eliot’s poetry is the sort of thing you ought to like, it seems, if you are to think yourself very clever.

Yet there is more to it than appearance, than the vanity of acquired taste. In an age of sensational surfaces, of a pixel-deep impressionism saturating our minds into a permanent state of trivial and tragic bafflement, Eliot’s poetry speaks beyond lyrics and rhyme and metre to the central question of time.

What is the point?

IL MIGLIOR FABBRO

We would not have the Eliot in verse we have today were it not for the “better maker”, Ezra Pound.

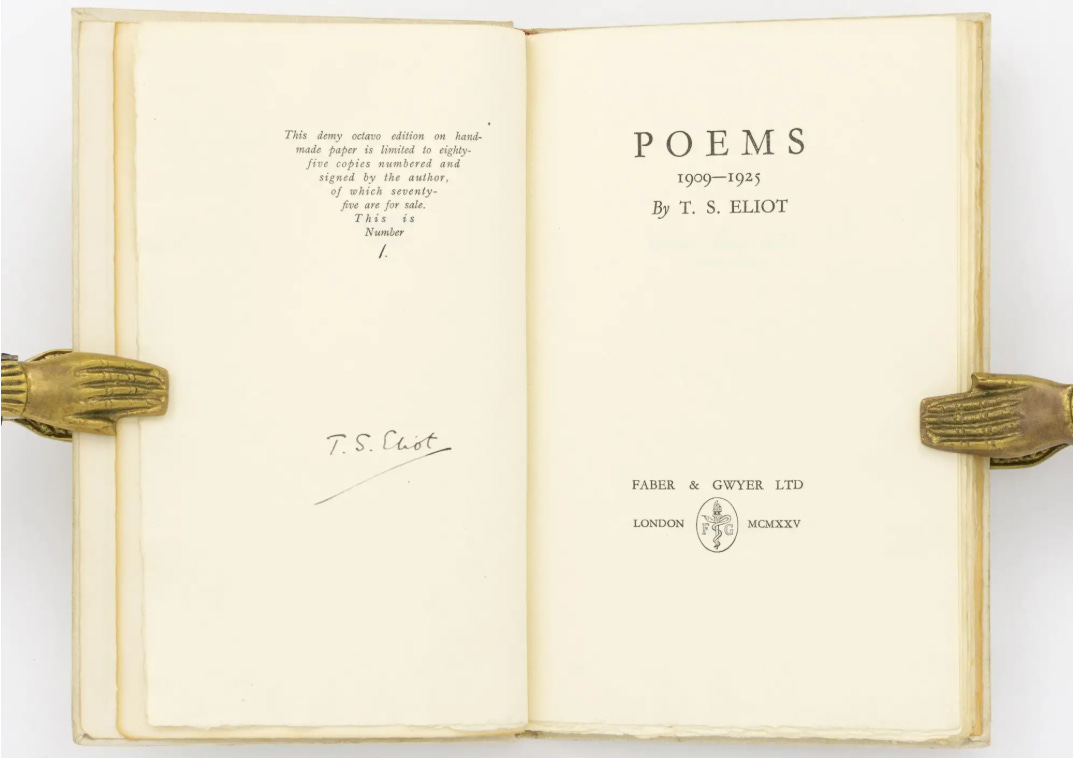

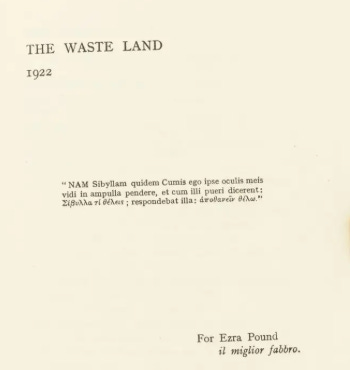

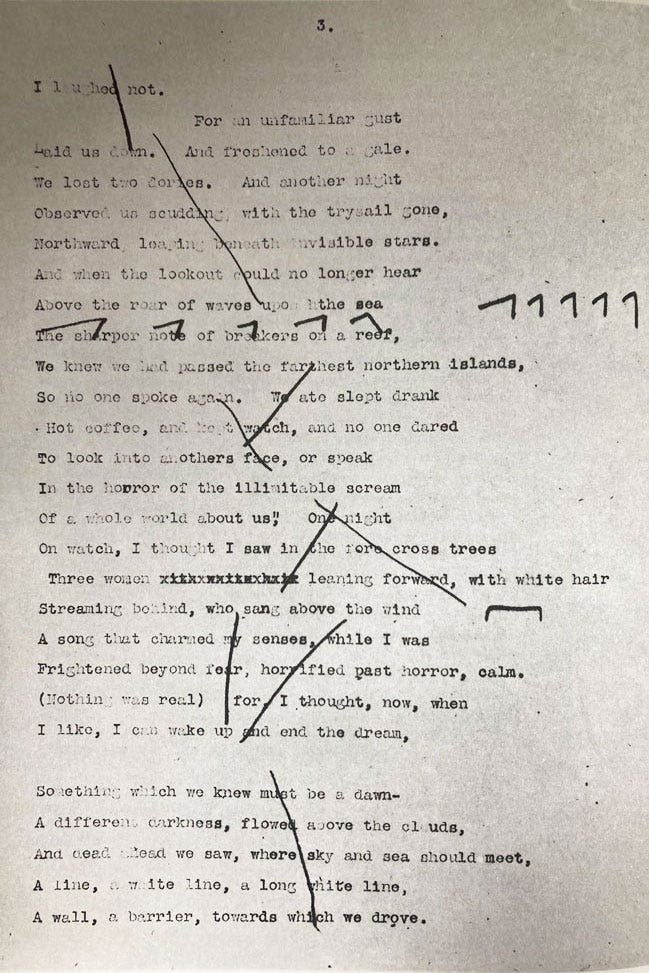

Pound edited Eliot’s early poem The Waste Land down from a palimpsest of doggerel to the masterpiece we know. Eliot dedicated it to him - styling him “Il miglior fabbro” - a phrase lifted from the Purgatorio of Dante Alighieri.

The dedication is routinely translated by the misprision “the better craftsman”.

Yet a “fabbro” is not just a craftsman, and craft is techne, giving a different sense entirely to the one I believe was intended.

Ezra Pound returned to poetry the idea that poems were something made. The word “poetry” comes from a Greek root (poiesis) meaning “making”.

In a review of Pound’s Cantos, perhaps the most ambitious pageant of the human experience ever attempted in words, William Carlos Williams said

“Pound discloses history by its odor, by the feel of it––in the words; fuses it with the words, present and past, to MAKE his Cantos.”

Ezra Pound was not a crafty technician but a maker. A poet. What words mean and what we take them to be today is a lesson again in how time and perspective, moment and meaning, relate to the changeless and the changed.

Poetry is the art of making a point. What is the point is something that has changed, changed utterly, as the terrible beauty of these modern times was born2.

ABC OF READING

Already I am off the point, already I must explain, as Eliot did himself,

“That is not what I meant at all”.

To be precise what I mean here is that Pound helped Eliot to do what he was doing himself: to restore to an age of machine-swift sensationalism in which the Self was presented as the Archimedean Point the duty of the poet to make sense of the world.

The start of this is that poetry is making.

Pound explained what poetry was in a simply titled book called “The ABC of Reading”.

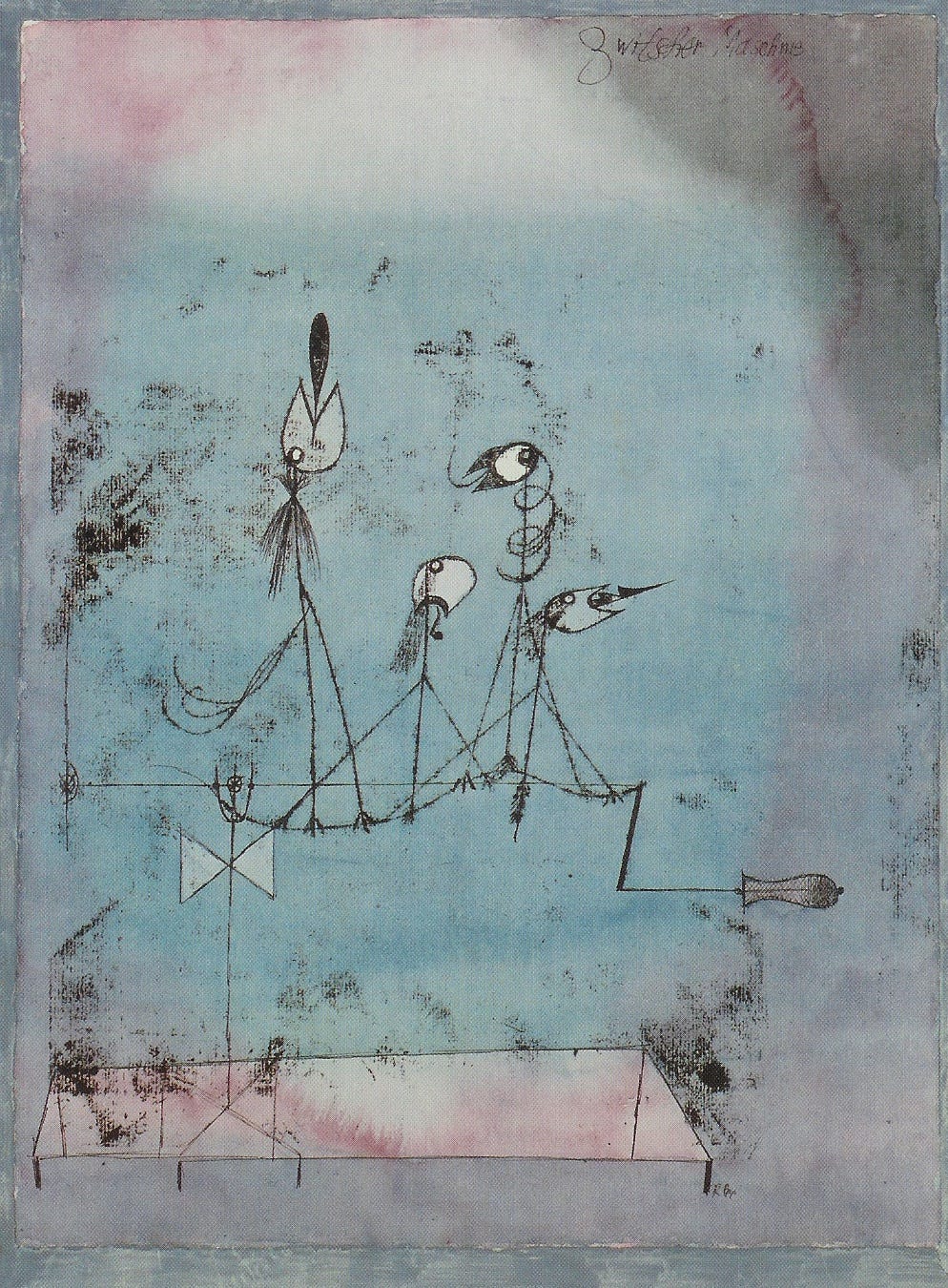

He said it had three elements - words, sounds and images.

Logopoeia - the making of words on the page - was the first. Which to choose, how to arrange them. Textbooks would call this lexis but there is of course more to it than mere choice between groups of letters.

It is how they are made to appear on the page, together - to show something more than their literal meaning.

Then there is melopoeeia, said Pound - the melody or music with which these words are charged.

Finally, phanopoeia - the making of images in the reader’s mind.

This is the reason Pound’s Cantos read like a spell, and are not merely words spelled out.

This gift he had, which revived the spirit of poetry beyond the efforts of even a man like Yeats, his near contemporary, explains why he could take the rough diamonds of Eliot and cut them into gems.

These Monday posts on the nature of our culture and its competition with our civilisation are paywalled because I could not make them without the support of paid subscribers.

If you would like to read them but cannot afford to pay me do send me an email saying “SKINT” and if I believe you, I will let you in with a free subscription.

frankwrighter@pm.me